Editor’s note

Sometimes, common usage of a term and its strict definition do not overlap as much as you would expect. Take the term ‘biodiversity hotspot’. This seems simple: a biodiversity hotspot is a region that is especially rich in biodiversity; in other words, rich in the number of species of organism (plants, animals, fungi, etc.). Wrong! A biodiversity hotspot, as defined by Conservation International, is a region that must meet two strict criteria to qualify as such:

- It must have at least 1500 vascular plants as endemics—which is to say, it must have a high percentage of plant life found nowhere else on the planet. A hotspot, in other words, is irreplaceable.

- It must have 30% or less of its original natural vegetation. In other words, it must be threatened.

One can argue that the first criterion is a bit confused, because it conflates absolute numbers with percentages. But it is the second criterion that causes the definition to conflict with common usage. A hotspot must not only be rich in (endemic) species, but it must also have only a small part of its original vegetation cover left. One of the surprising consequences of this strict definition is that New Guinea is not considered to be a biodiversity hotspot. That not only seems counterintuitive, but from a conservation perspective, it also seems counterproductive. Just because New Guinea currently has far more than 30% of its original vegetation cover left (although this is disturbed in many places), this does not mean that this favourable situation could not worsen rapidly. If one considers how much of the forest area of New Guinea is already given in concession to logging companies, the picture is shocking and the outlook bleak, especially in the lowlands.

More recently, a new concept has been proposed, that at first sounds like the opposite of a hotspot: a plant biodiversity darkspot (Ondo et al., 2024). However, a darkspot is not a region that is especially poor in plant species, it is one that is both rich in species and poorly known. Darkspots are regions where we can expect to find the greatest numbers of new species and new distribution records (the exact definition is more complicated than this; see the paper cited). It turns out that New Guinea is the most significant global plant diversity darkspot outside the neotropics.

How do we protect the plant diversity in a darkspot like New Guinea? Keeping the status quo would be desirable but is clearly unrealistic. A reasonable approach is to identify those areas that are especially rich in plant life and to focus conservation measures on these areas first. This approach is at the heart of the Tropical Important Plant Areas (TIPAs) programme, which is carried out at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, along with local partners (Darbyshire et al., 2017). This has been especially successful in several African countries, but there is also a New Guinea TIPAs project underway, which for now is focused on the Bird’s Head Peninsula in Indonesian New Guinea.

One factor in deciding if a certain area would qualify as a TIPA is the presence of threatened species. This, in turn, requires conservation assessments to be made for as many species as possible, which should be done according to the IUCN Red List criteria. Whereas policy makers can ignore vague statements such as “This area is very rich in species”, a statement such as “This area contains the following threatened species, of which X, Y, and Z are Critically Endangered according to IUCN criteria” is far more specific and thus harder to ignore. Detailed information also helps to show that each TIPA is almost always unique and irreplaceable.

It is not easy to make conservation assessments in a region like New Guinea, where so much land is still botanically underexplored, but it can be done, by considering the species’ ecology, known distribution, and known threats to the sites where it occurs or might occur. A recent paper suggests that three in four undescribed species are estimated to be threatened with extinction (Brown et al., 2023), and there are still many undescribed species in New Guinea.

Describing species new to science has always been the focus of the Malesian Orchid Journal, although I would have liked to see more ecological papers, as I have said before. Every new species is likely to be a threatened species (as is born out by the conservation assessments of two of the new species described in this volume), so that their description and publication are directly relevant for conservation. They provide fresh arguments for identifying TIPAs. Taxonomic revisions are no less valuable, because these give insight into the geographical distribution of species; without this knowledge conservation assessments cannot be made.

The present volume contains a mixture of taxonomic revisions and descriptions of novelties, and I hope these papers will contribute towards the conservation of the special places where the species occur. The revisions are all due to Ong Poh Teck (FRIM), who tirelessly works on revising the orchid flora of Peninsular Malaysia, which is not nearly as well known as we might think.

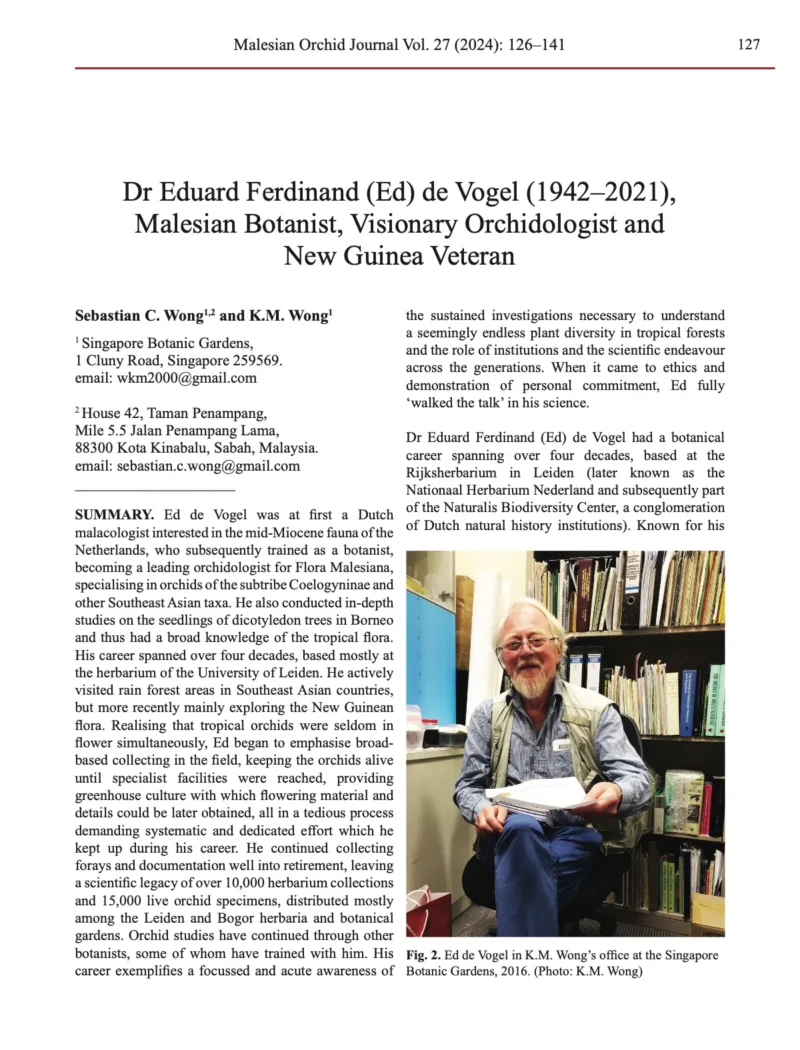

Finally, I am pleased that Sebastian Wong and Khoon Meng Wong have put together a biographical sketch of my late mentor Ed de Vogel, who had many friends in the Malesian region, as is attested by their fine article.

André Schuiteman

Kew

9 October 2024

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.